Alerts & Updates 10th Apr 2024

On March 12, 2024, the Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA) published the Report of the Committee on Digital Competition Law (CDCL Report) of the Committee on Digital Competition Law (CDCL) along with a draft of the Digital Competition Bill (DCB), inviting public comments until May 15, 2024. As a background, it was in December 2022 that the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Finance (Committee) had presented its report on ‘Anti-Competitive Practices by Big Tech Companies’ to the Parliament, after consulting stakeholders. The Committee’s key recommendations included the introduction of an ex-ante legal framework for large digital enterprises operating in India through the introduction of the ‘Digital Competition Act’. Following the Committee’s recommendations, the MCA appointed the CDCL to review the existing Competition Act, 2002 (Competition Act) and assess the need for a separate legislation governing the digital sector in India.

Some of the key features and provisions under the DCB are discussed below:

The DCB draws heavily from a similar legal framework adopted in the European Union (EU) (i.e., Digital Markets Act, 2022) and the proposed legal framework in the United Kingdom (UK) (i.e., Digital Markets, Competition, and Consumers Bill, 2023). The CDCL Report notes that ex-post enforcement provided for under the Competition Act may not be ideal to address the anti-competitive concerns in the digital sector mainly due to the following reasons:

a. An ex-post approach must be supported by an ex-ante framework: In India, there is no sectoral regulator to ex-ante monitor the activities of digital enterprises. The CDCL notes that an ex-post competition enforcement will work best when complemented with and supported by an ex-ante regulation, to provide an effective framework within which market players can operate.

b. An ex-post approach is time-consuming: In rapidly evolving markets, an ex-post enforcement does not always lead to optimal market correction. Further, ex-post inquiries are resource-intensive and time-consuming, which may result in the market irreversibly tipping in favour of the incumbent players and driving out competitors. According to the CDCL Report, such resultant harms cannot be remedied effectively under an ex-post legal framework and an ex-ante approach is likely to bring administrative efficiencies as well.

c. An ex-post approach addresses only narrow claims: Ex-post investigations are limited to the narrow claims under investigation and may not effectively address broader or repetitive anti-competitive conduct by an enterprise or similar conduct by different enterprises.

In contrast to the ex-post approach under the Competition Act, the DCB has proposed an ex-ante regulatory approach by setting out standards and rules for large digital enterprises and a framework for active monitoring to prevent anti-competitive conduct by such large digital enterprises.

The DCB would apply to enterprises providing ‘Core Digital Services’ (CDS) that meet the prescribed criteria and qualify as ‘Systemically Significant Digital Enterprise’ (SSDE). The following have been categorized as CDS: (a) online search engines; (b) online social networking services; (c) video-sharing platform services; (d) interpersonal communications services; (e) operating systems; (f) web browsers; (g) cloud services; (h) advertising services; and (i) online intermediation services.[1]

a. Designation of an enterprises as an SSDE: Under the DCB, an SSDE would be an enterprise with a significant presence in India in respect of the provision of CDS in India and with the ability to influence the Indian digital market(s). For an enterprise to be deemed an SSDE, it must meet tests of – (a) significant financial strength; and (b) significant spread (statutory thresholds).[2]

i. Significant financial strength test: An enterprise that meets any of the following thresholds under the relevant parameters, in the immediately preceding 3 financial years, will have met this test:

| Parameter | Applicable threshold |

| Turnover in India | ? INR 4000 Crores (~USD 482 million), or |

| Global Turnover | ? USD 30 billion, or |

| Gross Merchandise Value (Total value of goods or services, or both sold by, or through the intermediation of the enterprise through all the CDS) | ? INR 16000 Crores (~USD 1.93 billion), or |

| Global Market Capitalisation | ? USD 75 billion or its equivalent fair value of more than USD 75 billion calculated in any manner prescribed. |

ii. Significant presence test: An enterprise that meets any of the following thresholds under the relevant parameters, in the immediately preceding 3 financial years, will have met this test:

| Parameter | Applicable threshold |

| End user base in India (Natural or legal person using the CDS other than a business user) | ? 1 crore, or |

| Business user base in India (Natural or legal person supplying or providing goods or services, including through the CDS) | ? 10,000 |

b. CCI’s power to designate: In cases where neither of the tests described above is met, the DCB empowers the CCI to designate an enterprise as an SSDE based on certain factors provided under the DCB including (i) volume of commerce; (ii) size & resources of the enterprise; (iii) dependence of users; and (iv) network effects & data-driven advantages (relevant factors). Several of these factors are the same as the factors for assessment of dominance under the Competition Act.

If an enterprise meets the criteria for qualifying as an SSDE in respect of one or more CDS, the DCB mandates that it must notify the CCI within 90 days of meeting the criteria including in relation to other enterprises in its group, that are directly or indirectly involved with one or more CDS. Such related enterprises would be categorized as an ‘Associate Digital Enterprise’ (ADE).

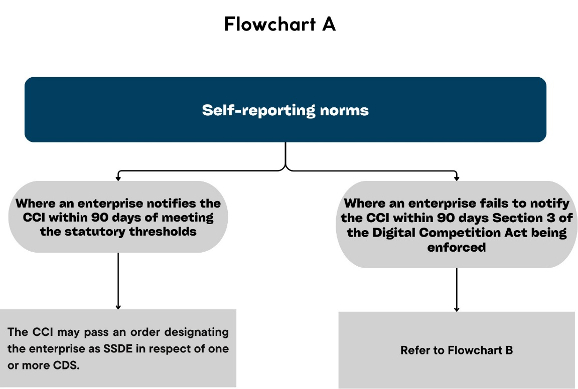

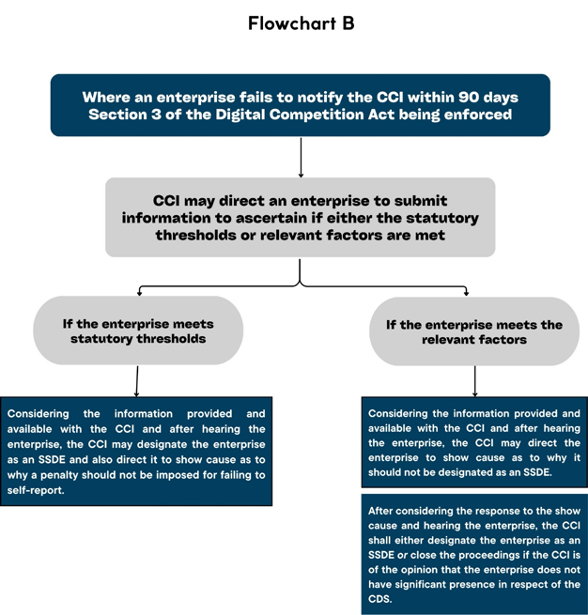

Under the DCB, a failure to notify the CCI may lead to a direction to furnish such information along with a show cause that could lead to the imposition of a penalty. The detailed procedure in respect of the designation of an enterprise as an SSDE is available in Flowcharts A and B in Annexure I.

Designated SSDEs as well as ADEs must comply with obligations under the DCB, its rules, and regulations. The DCB currently provides for general obligations applicable to SSDEs/ADEs. Subsequently enacted rules and regulations will provide for further tailored obligations for each CDS as well as for certain categories of SSDE/ADE.

a. General obligations:

The DCB sets out the following general obligations for SSDEs/ADEs:

i. Fair and Transparent Dealing: SSDEs/ADEs must operate in a fair, non-discriminatory, and transparent manner with end users and business users.

ii. Self-preferencing: SSDEs/ADEs cannot, directly or indirectly, favour their own products, services, or lines of business or those of –

a) related parties, or

b) third parties (3Ps) with whom SSDEs/ADEs have arrangements for the manufacture, sale of products, or provision of services by 3P business users on the CDS.

iii. Data usage:

a) SSDEs/ADEs cannot directly or indirectly use or rely on non-public data[4] of business users operating on their CDS to compete with business users on the SSDE’s identified CDS.

b) Without the consent of the end-user or the business user, SSDE cannot-

i. intermix or cross-use the personal data of end users or business users collected from any service or CDS, or

ii. permit the usage of such data by a third party.

iv. Restricting 3P applications: SSDEs/ADEs cannot restrict or impede the ability of end users to download, install, operate or use 3P applications or other software on its CDS. They must also allow end users and business users to choose, set, and change default settings.

v. Anti-Steering: SSDEs/ADEs cannot restrict business users from directly or indirectly communicating with or promoting offers to their end users or directing their end users to their own or 3P services, unless such restrictions are ‘integral’ to the provision of the CDS.[5]

vi. Tying and Bundling: SSDEs/ADEs cannot require or incentivise business users or end users of the identified CDS to use one or more of the SSDE’s other products or services or those of:

a) related parties; or

b) 3Ps with whom SSDEs/ADEs have arrangements for the manufacture, sale of products, or provision of services by 3P business users on the CDS alongside the use of identified CDS unless the use of such products or services is ‘integral’ to the provision of the CDS.[6]

vii. Anti-circumvention: SSDEs must not engage in behavior that undermines effective compliance with obligations under the DCB and the rules and regulations in any manner. Further, SSDEs cannot directly or indirectly prevent or restrict business users or end users from raising issues of non-compliance with the SSDE’s obligations under the DCB.

b. Other obligations as specified by CCI: The DCB allows the CCI to specify differential obligations for various SSDEs based on factors including the nature of the market and the number of users in India and may also specify differential obligations for SSDEs and their ADEs.

a. Penalties:

The CCI can impose the following penalties for violation of the DCB:

| Contravention | Penalty |

| (i) Failure to meet the obligations under the DCB or the rules and regulations.

(ii) Circumvention from requirement to designate. |

Up to 10% of the global turnover in the preceding financial year. |

| If an enterprise fails to notify CCI of meeting the prescribed thresholds of significance presence. | Up to 1% of the global turnover. |

| (i) If SSDE/ADE provides incorrect, incomplete, wrong or misleading information to the CCI; or

(ii) If SSDE/ADE refuses to provide information or cooperate with the DG during the investigation. |

Up to 1% of the global turnover. |

| Penalty on individuals: The following individuals can be penalized:

(i) who is in-charge of a contravening SSDE or ADE. (ii) who is a director manager, secretary or any other company officers, on whose consent, connivance or neglect the contravention of the DCB took place. |

Up to 10% of the average income for the last three preceding financial years. |

b. Remedies:

In addition to the penalties described above, the DCB also empowers the CCI to – (1) direct an enterprise to discontinue and not resume any contravening conduct; (2) direct an enterprise to modify the specified conduct; and/or (3) pass any other such order as it may deem fit. The enforcement framework under the DCB borrows from the Competition Act and also encompasses the recently introduced provisions for settlement and commitment.

As under the Competition Act, appeals under the DCB would also lie before the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal (NCLAT) and subsequently, before the Supreme Court of India.

An ex-ante regulatory approach for digital markets – Need of the hour?

a. Potential impact on growth, innovation, and consumer interests: Digital markets are typically characterized by rapid growth, and innovation that require a certain degree of freedom and environment to constantly evolve. The growth and innovation in the digital sector have a significant impact across other markets. The impact of an ex-ante regulation on the digital market(s) will certainly be felt on the performance and growth of other markets. The Government must carry out a more thorough and detailed analysis to fully appreciate and understand the potential impact of the adoption of a law of this nature in light of the objectives that this proposed law is set out to achieve. Accordingly, both timing and the provisions of this law should be well-considered and well-researched. While timely interventions may be required in certain scenarios to ensure necessary market corrections, a premature or an overly intrusive approach has the potential to stymie innovation and hamper competition in such markets. Such interventions will not only harm other growth and development of markets but will also cause harm to consumer interests.

b. Parallel scrutiny under the DCB and the Competition Act: Once enforced, qualified entities operating in digital markets would have to strictly comply with two parallel regimes, the DCB and the existing Competition Act. This will not only impose a high degree of compliance burden on the entities that fall within the ambit of both the statutes but will also likely to lead to complicated enforcement mechanisms that could pose challenges both for the industry as well as for the CCI.

c. Boost in technical and administrative capabilities: Given the untested nature of the ex-ante competition regime even at the global level, there is limited to no guidance available for the CCI to follow and learn from. For a law of this nature to be enforced with the desired results and to meet the identified objectives, the Government must ensure that the CCI is equipped with suitable technical and administrative capabilities. A deficiency in proper resources will have serious negative implications on the enforcement of two very critical legislations which could defeat the objectives of both legislations and impact the markets and consumers negatively.

d. Potential for regulatory overlaps: The framework set out under the DCB, including obligations on SSDEs and ADEs, may also overlap with other regimes such as that under the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 (Data Protection Act). The Data Protection Act provides mechanisms for the processing of personal data and penalties for failure to observe the data protection obligations. Therefore, a breach of data usage obligations for end-users’ data may result in penalties under both- Data Protection Act and DCB. Some of these foreseeable areas of regulatory overlap must be addressed and reconciled before the ex-ante regime under the Digital Competition Act comes into force.

Annexure I

A visual representation of the self-reporting obligations and designation provisions.

We hope you have found this information useful. For any queries/clarifications please write to us at insights@elp-in.com

Ravisekhar Nair, Partner – Email – ravisekharnair@elp-in.com

Abhay Joshi, Partner, Email – abhayjoshi@elp-in.com

Aayushi Sharma, Senior Associate, Email – aayushisharma@elp-in.com

Bhaavi Agrawal, Associate, Email – bhaaviagrawal@elp-in.com

Pavan Kalyan, Associate, Email – pavankalyan@elp-in.com

[1] The list of CDS can be amended by the Central Government, in consultation with the CCI.

[2] (a) If a party either does not maintain or fails to furnish data regarding the statutory thresholds, CCI would still be able to designate that enterprise as an SSDE if it meets either of the statutory thresholds.

(b) The Central Government, in consultation with the CCI, would re-examine the statutory thresholds every three years.

[3] An enterprise cannot directly or indirectly segment, divide, subdivide, fragment, or split to circumvent the thresholds. The CCI may direct any enterprise to furnish further information and may pass an order designating the enterprise as an SSDE.

[4] Non-public data is defined as any aggregated and non-aggregated data generated by business users that can be collected through the commercial activities of business users or their end users, on the identified CDS of the SSDE.

[5] CCI can specify through regulations when the nature of restrictions may be considered ‘integral’ to the provision of a CDS.

[6] CCI can specify through regulations when the nature of restrictions may be considered ‘integral’ to the provision of a CDS.